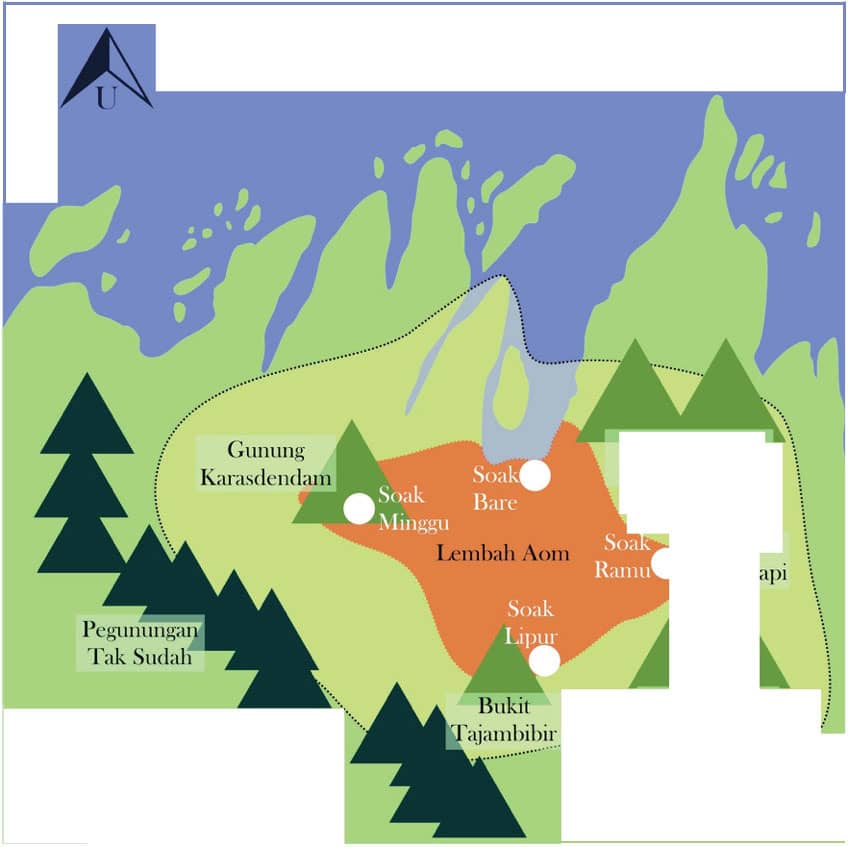

The population of Runcuk horse was spread in the western zone. Throughout all generations, Orang Runcuk believed that horse was the carrier of their ancestors’ souls within their journey to moksa. Instead of releasing and setting Runcuk horses free in their wild habitat, Orang Runcuk performed a tradition to hunt the male horses that commonly led the herd of Runcuk horses.

Orang Runcuk practiced a specific technique to be able to identify the leader of the herd of Runcuk horses by a kind of observation usually called magonggei. Magonggei was performed by surrounding the herd of Runcuk horses and terrorized them. Clamorous masculine cries and ancient mantras coalesced with intimidating movements acted upon Runcuk horses would ravage their formation and disperse them. Within such chaos, the one horse that reacted by acting fearlessly yet defensively (usually cried the most noisy and ear-piercing shout, as lifting its two forelegs—instead of running in panic) was the leader of the herd that would later be the target of the game. Orang Runcuk would hunt it down, barefooted, with spears as they kept shouting boisterously to threaten the horse.

Orang Runcuk believed that their honour to their ancestors’ souls carried by Runcuk horse had to be released along with the death of Runcuk horses’ herd leader during a hunt conducted in the noon towards the full moon. Orang Runcuk called the leader of the herd as “The Strident Runcuk Horse”. They believed that the spirit of The Strident Runcuk Horse was the supernatural steed for the ancestors’ spirits in every full moon.

The hunting of The Strident Runcuk Horse was a complex ritual that involved almost all adult men in the village around the foot of Mount Tanarimba. The hunting ritual was usually begun with the old shaman of the village reciting ancient mantras; he had purged himself for the mantra reciting by fasting and not talking for 3 days.

The captured Strident Runcuk Horse would be immediately brought to be purified in the village; they would perform ‘ponge’ (beheading the horse so that it would not be strident in the spirit world) and take the horse’s heart to be eaten by those brave men who had conducted the exhausting hunting.

Runcuk horse’s heart was believed to increase stamina, faith, and sexual desire. This tradition can still be seen in several villages at the foot of Mount Tanarimba. However, this practice indeed encountered some significant shifts, particularly in the coastal area which had interacted with economic liberalization managed by the local elites and colonial government.

In the more advanced coastal area, common Runcuk horses (not the leader of the herd/The Strident Runcuk Horse) were intentionally hunted in ordinary moments to be domesticated, and the hearts were taken as commodity. The practice of trading Runcuk horses’ hearts were common in this area, because after all, the local society strongly believed the benefit of Runcuk horses’ hearts within their everyday life.

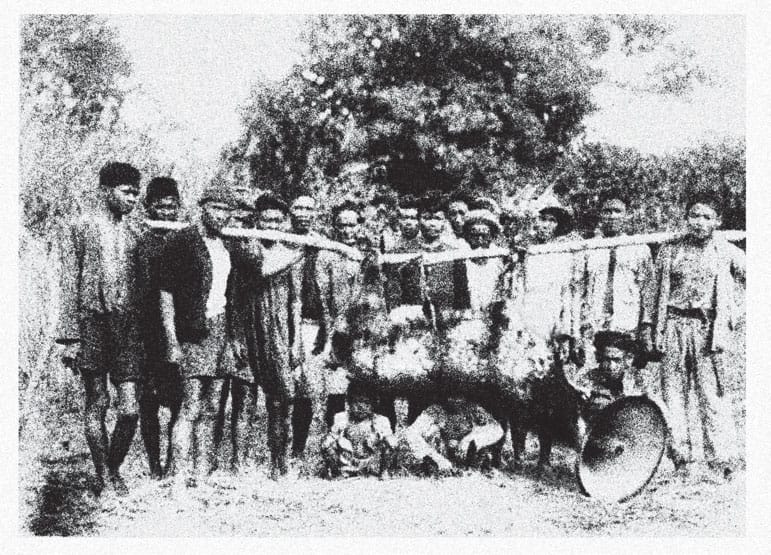

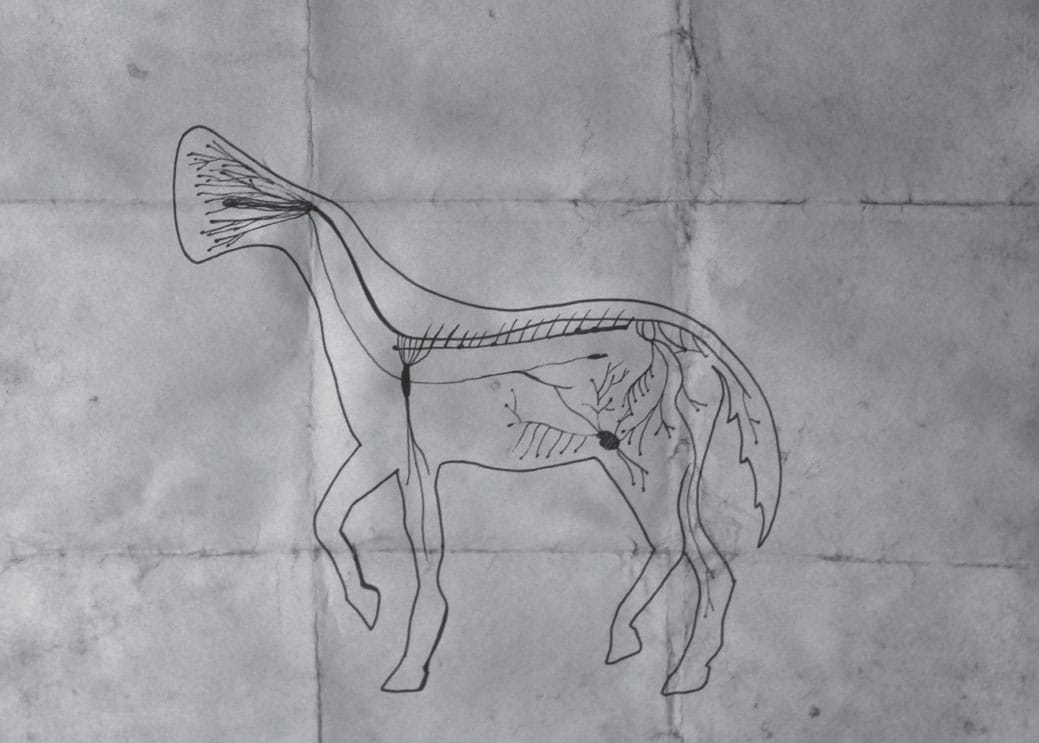

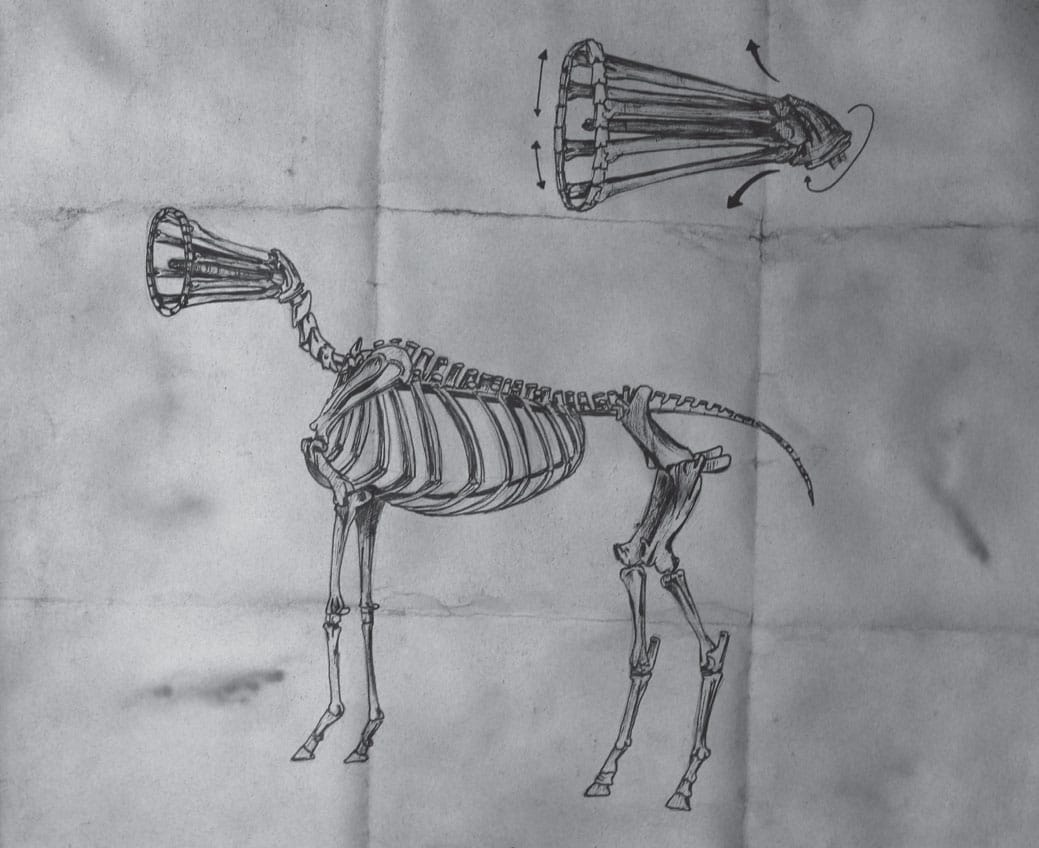

Another photograph officially published by TPTR as the means to create the myth of The Strident Runcuk Horse (Archive of CTRS).

The Megaphone-Head Strident Runcuk Horse: Stuttering in Welcoming the Forced Modernity

There was an interesting fact that existed and was believed, related to the contact of industrialization and modernization brought by the local elites and colonial government into Tanah Runcuk. Since the arrival of modern machines and devices smuggled from Europe, Orang Runcuk had encountered a great culture shock. They seemed to be baffled on how to position those “strange” devices into the mystical logic they had been living in their everyday spirituality. Irons were splashed with holy water and anointed with ancient mantras. Even at the most extreme point, The Strident Runcuk Horse that was getting rare was eventually mystified in a very hybrid and naive imagination. Stern and Wallach, with a great enthusiasm, described The Strident Runcuk Horse imagined by the villagers, as the megaphone-head Strident Runcuk Horse. People called it Jaran Amogan.

People needed something to believe in, as the affirmation of their existences in the middle of their cosmological universe. The presence of modernity enforced by the colonial government in a lopsided manner largely contributed to create some shocks and collisions of the meaning of body and collective memory of Runcuk people—who held firmly to the tradition. Such collisions later negotiated one another and finally created another space for the people to remain finding themselves within a very personal and spiritual—in this context: mystical—level. Thus, the model was manifested into Jaran Amogan, that was believed as the supernatural horse that brought a message from the ancestors to the living human who still coped with the worldly things.

This irrational indication turned out to receive a serious response from the colonial government and local elites. The colonial government published some pictures and photographs of Jaran Amogan, and then frequently summoned traditional shamans to conduct the celebration of honour to Jaran Amogan. The rulers intentionally reproduced hybrid visual imaginations of this megaphone-head horse, with the support from literary texts produced by the local elites of the kingdom in the form of new mantra scripts and some rituals to keep Orang Runcuk away from rationality.

One of the scripts (hummed as a mantra on the days of birth, marriage, and death) from Tanah Runcuk presenting the figure of Jaran Amogan is the script of Malalongkė Pacah:

“hai’ing khu mawė mi ka lamm ka lang ho

Ulėkaba sok malalongkė

sokmelaka bo

Poh raham ka amogan Jaran jaraga amogan

Hė lammo thakka arėnnemo thak ka lang

Irakkanne sak kai’ matalong ka long kamogan

Nahha eo kai pacah matalong thak ka lang

Ampo alėkaba sok malalongkė

sokmelaka bo

haiing khu mawė mi’ ka lamm ka lang ho”

The script narrates the last king in Tanah Runcuk who met all spirits of their ancestors, the warlord, and the ruling queen of the ocean by riding Jaran Amogan to the highest sky through the peak of Mount Kawaruncing. The encounter resulted an exhortation for those who were still living to always surrender to life and preserve the tradition and ritual at the foot of the mountain so that salvation was with the entire living things.

The script showed the multilayered hierarchy of power ranging from the high world (ancestors’ spirits), the ruling elite (the latest king), and the people as the low world. The top-down power relation, from the high world to the low class with the intercession of the king (as the extension of their ancestors and supernatural rulers’ hands) can be interpreted as the model of ideological reproduction and power legitimacy which were immaterial and tended to be irrational.

Through the rites (required by the ancestors’ spirits to the people with the intercession and under the responsibility of the king), the people were interpellated and maintained to remain in their own social class (surrendering, for their salvation).

Who else were benefited by this illusion but the elites and the rulers?

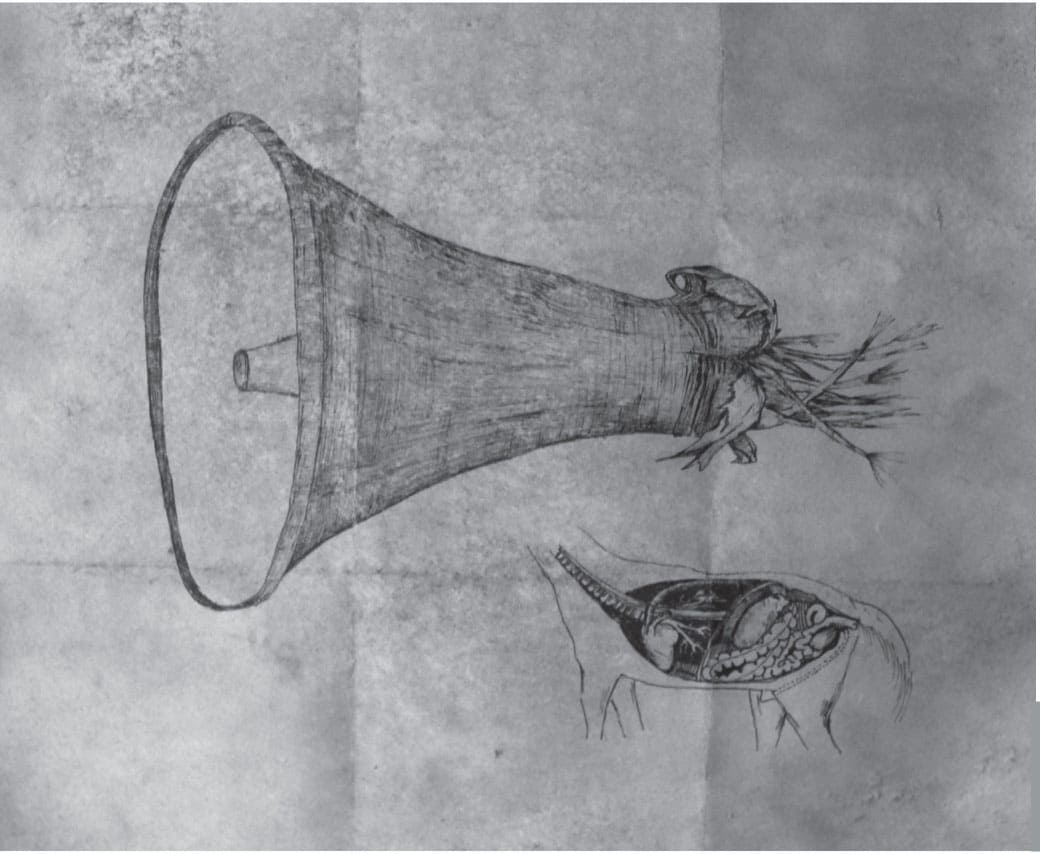

Stern Jr.’s illustration of Runcuk horse. The discovery of this document raised suspicion on the ambivalence of partisanship and his orientalist view during his stay in Tanah Runcuk.

The Illustration of the Megaphone-Head Strident Runcuk Horse’s Morphology, that was actually a myth created by the colonial government.

It still needs further research on: whether Stern Jr. was affiliated with TPTR, or whether this illustration was merely typical naive, orientalist amazement and admiration of foreign, exotic, and adventurous Tanah Runcuk.

Some experts related this tendency—just like the Europeans living in Tanah Runcuk at the time (and the previous time), with Chateubriand, who was recently known through the discovery of his manuscripts summarized in the “Letters from Penang”.

(Archive of CTRS)